More than 1.7 million Americans were diagnosed with cancer in 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Experts say the national goal to cut the cancer mortality rate in half within 25 years is ambitious but possible.

By Lauren Berryman

In March 2019, Shelby Ellis did not feel like herself. She felt tired, developed anxiety and gained weight despite eating well and working out more than ever.

She scheduled an appointment with her primary care doctor to test her hormone levels, although she said her doctor thought these tests were unnecessary.

As she feared, Ellis’ thyroid levels came back abnormal. But after a second round of tests, her thyroid levels were normal. Ellis’ doctor told her nothing was wrong.

“I had to really advocate for myself in those appointments because deep down I knew there was something wrong,” Ellis, now 24, said in a recent interview.

After an ultrasound and biopsy, what Ellis thought was hypothyroidism turned out to be papillary thyroid cancer.

The day after the biopsy confirmed this diagnosis in August 2019, surgeons removed her thyroid, a butterfly-shaped gland that wraps around the throat. Five days later, she moved into college to start her senior year at Wake Forest University.

Shelley Fuld Nasso, CEO at the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, has worked in cancer advocacy for more than 15 years.

“We hear from survivors all the time that the first year after treatment was harder than the treatment itself because they’re left to put back the pieces of their lives,” Fuld Nasso said.

Ellis said some people have told her thyroid cancer is the best cancer to get. And while she is glad her cancer is in remission, she admits surviving cancer comes with challenges.

“People just assume once you’re cured that you’re fine,” she said. “But you have all these recurring thoughts. My biggest one is I’m always afraid it’s going to come back or I’m going to get it somewhere else,” like in her lymph nodes, she said.

Tackling cancer in the US

Living with cancer and surviving cancer bring a host of challenges to patients and families. President Joe Biden, whose son Beau Biden died of brain cancer in 2015, relaunched the Cancer Moonshot Initiative on Feb. 2. This plan aims to cut the cancer mortality rate in half within 25 years and improve the quality of life for those living with and surviving cancer.

The initiative, first launched in 2016 under the Obama-Biden Administration, intends to accelerate cancer research, encourage cancer screenings, increase funding and address health inequities to reduce the number of people dying from this disease – which is currently the second leading cause of death in the United States.

“Many of us were initially skeptical that it could deliver,” Dr. Peter Adamson, a pediatric oncologist who was appointed to the Cancer Moonshot Blue Ribbon Panel in 2016, said. “At the time, nothing was getting through Congress, but the Vice President [Biden] was rightly convinced that cancer cut across party lines.”

Doctors and researchers explain progress made in a relatively short amount of time toward addressing cancer has already come a long way.

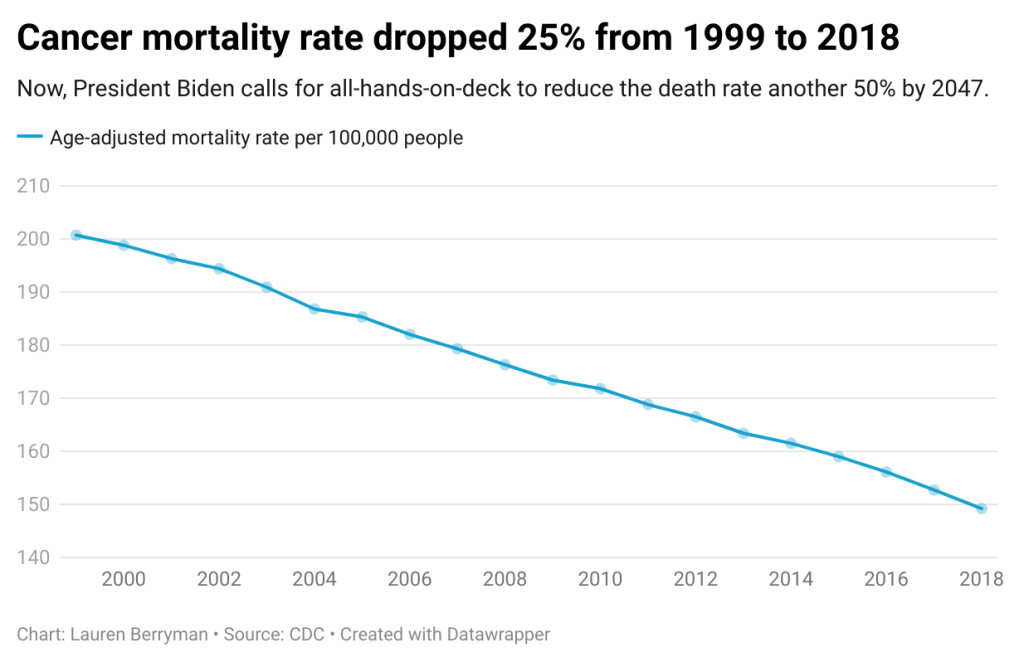

From 1999 to 2018, CDC data shows the age-adjusted cancer mortality rate per 100,000 people decreased 25% in the United States. Now, Biden wants to cut today’s rate in half.

Adamson, who now leads cancer drug development at Sanofi, points to the approval of the drug imatinib in 2001 as the pivotal event leading to increased cancer survival rates.

This drug, also called Gleevec, improved outcomes for adults with chronic myelogenous leukemia, a blood cancer which about 20,000 Americans are diagnosed with per year. Gleevec more than quadrupled the survival rate from 22% to 90%, according to the American Cancer Society.

Adamson said this was the first of many targeted therapies to develop and marked a “fundamental change” in how doctors treat cancer. Researchers study the target and the cancer before developing a drug rather than coming up with a treatment and seeing if it works.

He also said the rise of immuno-oncology, or treatments that use one’s own immune system to fight cancer, has played a significant role in improving cancer outcomes.

“What we considered ‘undruggable’ five years ago, five years from now are probably going to be ‘druggable,’” he said.

Challenges to addressing cancer

Even with medical advancements, there are hurdles when it comes to cancer diagnosis and treatment.

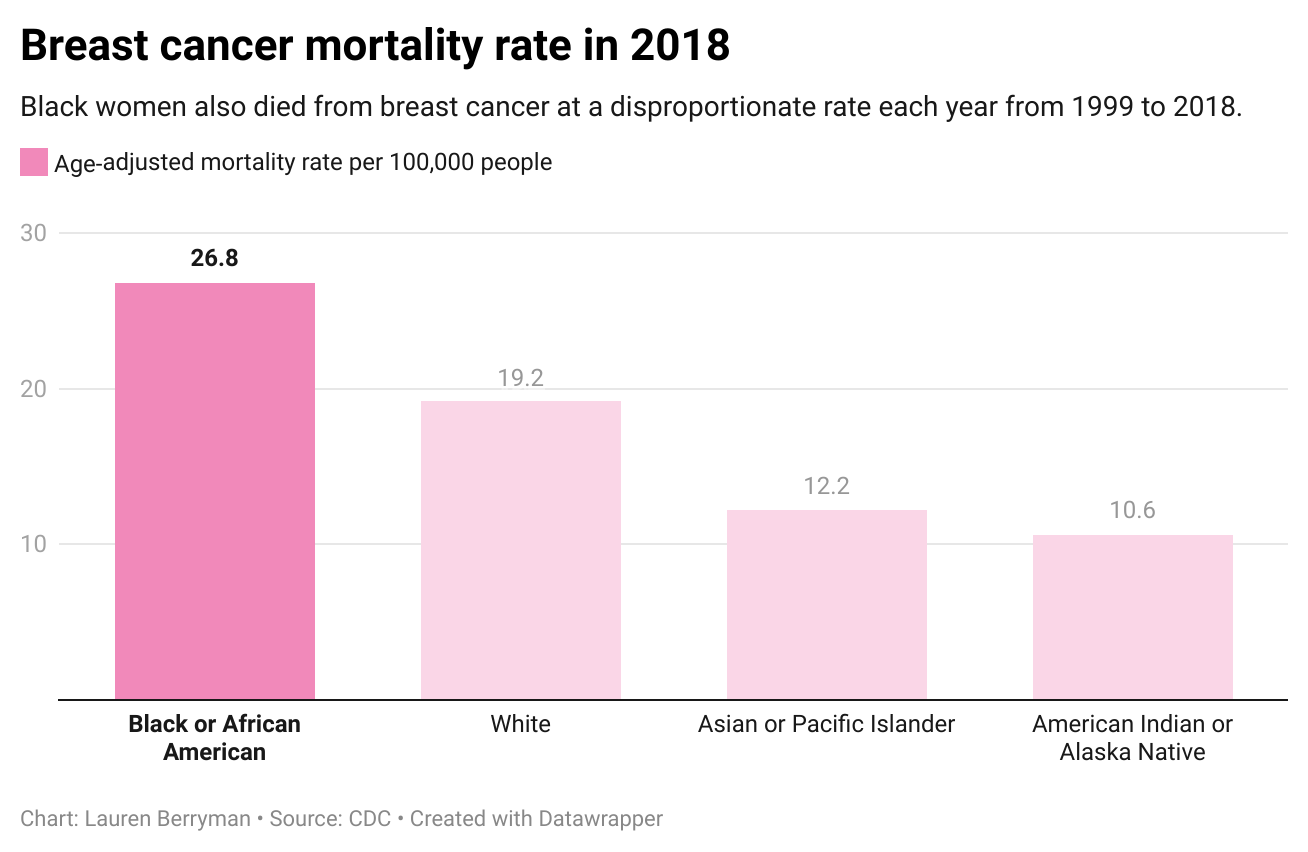

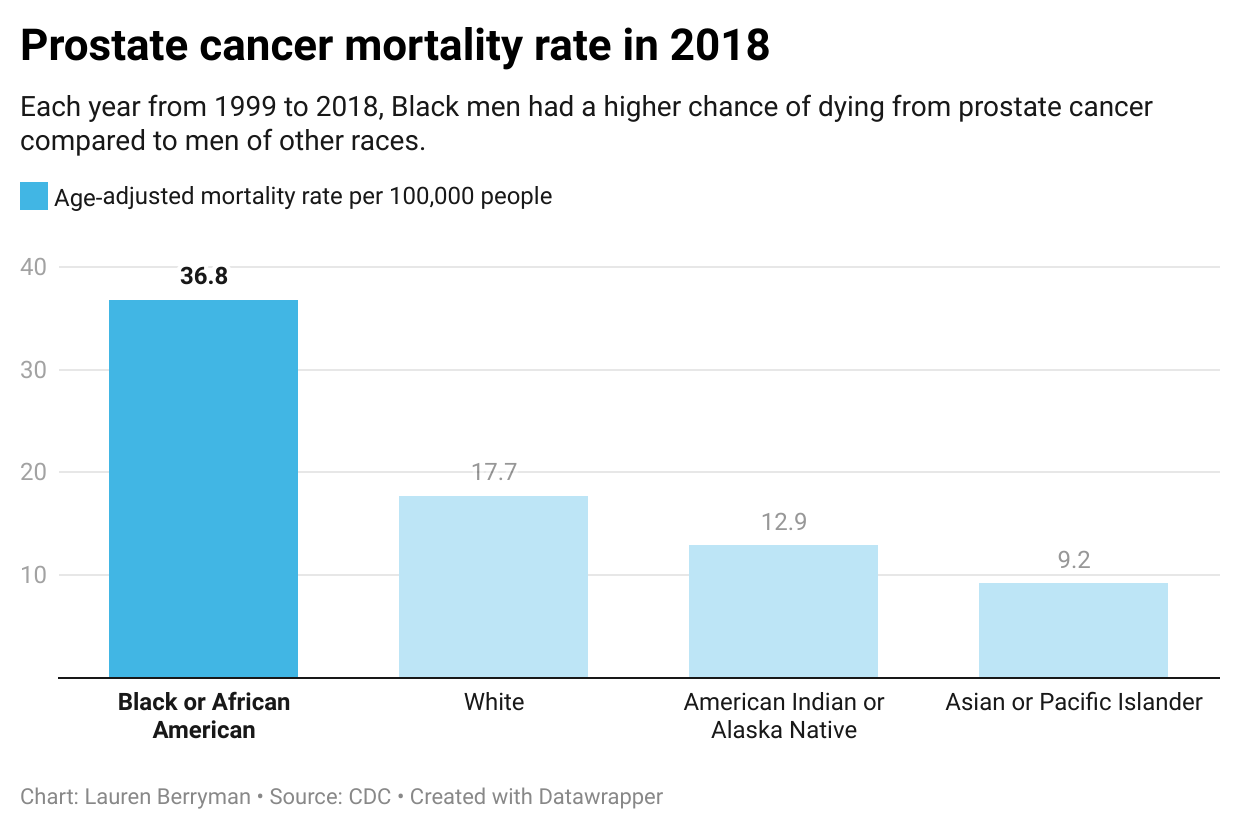

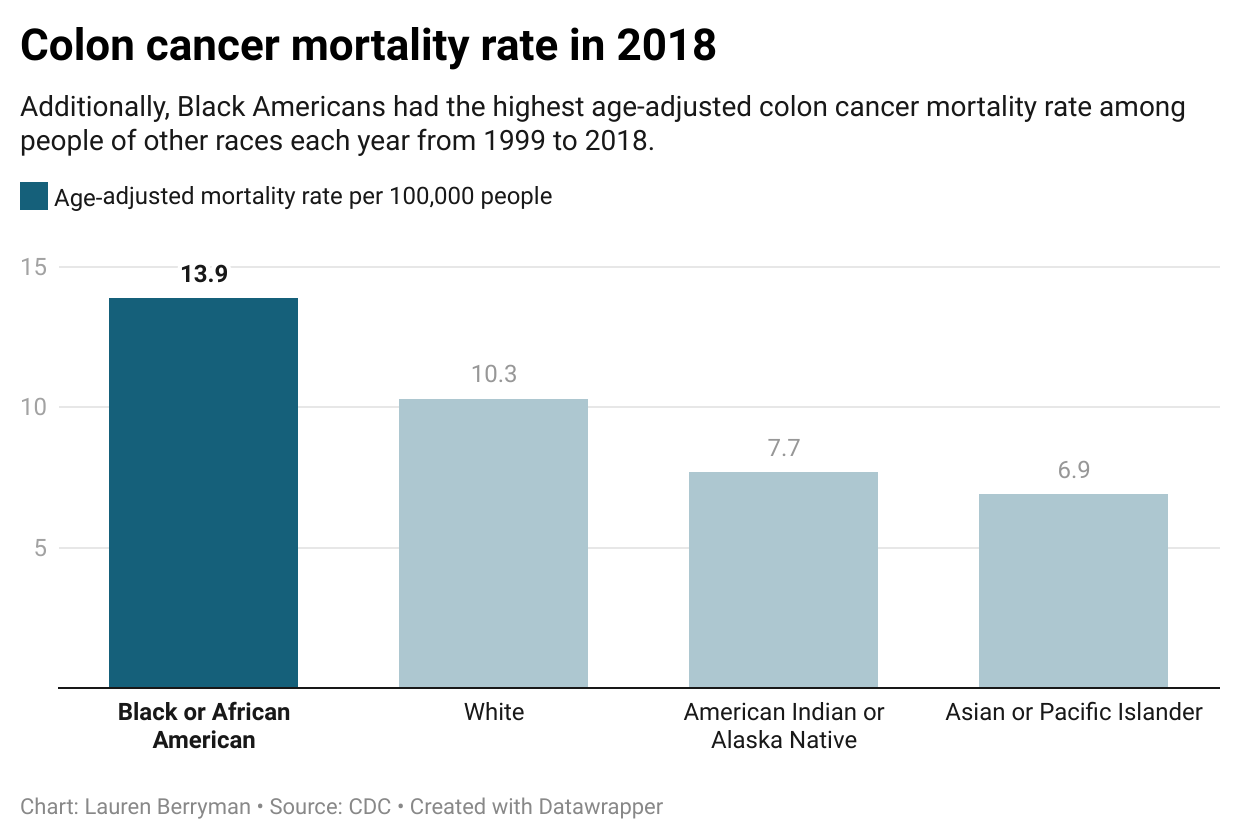

CDC data shows that each year from 1999 to 2018, Black Americans have been disproportionately affected by cancer. They face lower survival rates for breast, prostate and colon cancers — some of the most common.

Erin Linnenbringer, assistant professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis’ Institute for Public Health, researches the intersection of genetic and social risk factors that contribute to these disparities.

Some people of color lack trust in the medical system because of the history of racism in medicine or because of their own direct experience with discrimination, Linnenbringer said.

Caitlin Donovan, the senior director of public relations at the National Patient Advocate Foundation, also explained that one’s race, income and address impact access to care.

“People who are white are more likely to get access to clinical trials,” Donovan said. She added it is important to ensure people of color, women and those living in rural areas have equal access to clinical trials so they are representative of who would use the drug.

The implications of Covid-19 pose additional burdens on addressing cancer in the country.

From January to July 2020, nearly 10 million Americans missed routine cancer screenings compared to data from 2019, according to a report by the American Association for Cancer Research released last February. With early detection critical for improved cancer outcomes, those who work in the cancer community are worried about the lack of screenings during the pandemic.

“There’s a lot of concern that we’re going to start seeing an uptick in both diagnoses and later stages of those diagnoses,” Linnenbringer said.

“I think we’re going to see an increase in cancer mortality,” Adamson also said.

Covid-19 has proved to be not only a public health threat but also a political issue. People across the country are divided on vaccine mandates. Donovan at the National Patient Advocate Foundation raised the concern about how that debate could trickle into other aspects of health.

“How many families now aren’t getting the HPV vaccine? Are we going to see a spike in cervical cancers among kids who are of that generation?” she asked.

Glimmers of hope

While Adamson is also concerned about the ramifications of the pandemic, he sees a silver lining.

He thinks mRNA technology, which was used to create the Pfizer and Moderna Covid-19 vaccines in record time, could advance cancer therapeutics.

“I am optimistic,” Adamson said about whether he thinks the Cancer Moonshot Initiative can be achieved. “I do think that science is at the right place. As far as how quickly it’s moving, it can deliver.”

The specific details of the initiative have not been determined. Fuld Nasso at the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship hopes to see increased funding toward more holistic survivorship care. This care would include patient-tailored plans to aid the physical, emotional and financial effects of cancer.

Ellis, who has been in remission for almost three years, knows firsthand that better patient advocacy is crucial. Motivated to help others dealing with cancer, she now works at the American Cancer Society where she raises awareness and supports fundraising efforts which drive cancer research.

“There is no upside to cancer,” Donovan said. “Cancer is not a gift. Cancer is a diagnosis that can bring a heavy physical and emotional burden. But the people I work with who have cancer or are dealing with cancer are incredibly hopeful people.”